by Henrietta Cullinan

20th April 2020

As Kabul enters a third week of strictly-enforced lockdown, what do the restrictions mean for those living below the poverty line?

The first item on everyone’s minds is food. Some fear that, as flour prices rise, the small, local bakeries will close. ‘It is better to die of the coronavirus rather than die of poverty,’ says Mohammada Jan, a shoemaker in Kabul. Jan Ali, a labourer, laments, ‘Hunger will kill us before we are killed by the coronavirus. We are stuck between two deaths.’

Even without the disruption caused by the pandemic, nearly 11 million face acute food insecurity, according to UN projections. For the thousands of street children and casual labourers in Afghanistan, no work means no bread. For the poor in urban areas, the main priority will be to feed their families, which means being out in the street, looking for work, money and supplies. People are likely to be more worried about starving to death than about dying from the coronavirus. ‘They are too busy trying to survive poverty and upheaval to worry about a new virus’

With prices of wheat flour, fresh fruit and nutritious food items rising fast and no government control of food prices, there is a real danger of famine. Border closures, intended to restrict the spread of the virus, mean international supply lines of oil and pulses, mostly from Pakistan, will be severely restricted. Even though many farmers are optimistic for this year’s harvest, after plentiful snows and rains this winter, the virus could hit them just as the harvest starts in May.

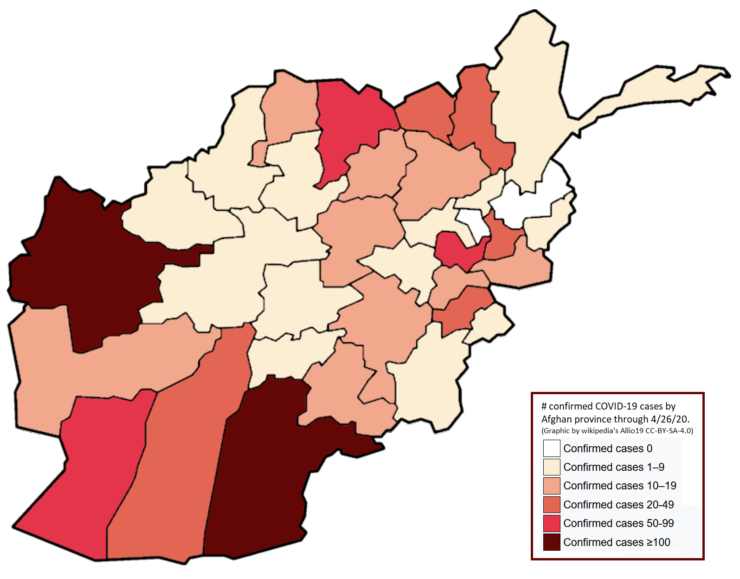

At the time of writing, there have been 1,019 confirmed corona virus cases and 36 reported deaths, although with limited testing and many not seeking health care when sick, the actual figure must be much higher. The provinces most affected are Herat, Kabul and Kandahar.

The heart of the outbreak is in Herat, the busy border town from which, normally, thousands of Afghans, mostly young men, cross into Iran in search of work. Following fatalities and lockdown in Iran, last week alone 140,000 Afghans recrossed the border into Herat. Some are escaping the coronavirus itself, others have lost their jobs because of the lockdown so they have nowhere to go.

In Herat, a three-hundred-bed hospital has just been built to cope with the new cases. Afghanistan has set up new testing centres, laboratories and hospital wards, even roadside hand washing stations. The World Bank has approved a donation of $100.4 million, to provide new hospitals, safety equipment, better testing and ongoing education about the virus. The first medical packs from China, of ventilators, protective suits and testing kits, arrived in Afghanistan last week.

Many Western NGOs, however, have had to stop work as their staff has been ordered home by their own countries and there is a shortage of doctors trained in the intubation procedures needed to help COVID-19 patients.

Afghanistan’s 1 million displaced people [IDPs] will be disproportionately affected by COVID-19. For those in camps, overcrowding means it is almost impossible to maintain social distancing. Poor sanitation, and scant resources, sometimes no running water or soap means basic hygiene is difficult. For migrant workers, a lock down means both their jobs and accommodation suddenly disappear; they have no choice but to return to their village, causing huge numbers of people to be on the move.

Commentators International Alert and Crisis Group analyse the fall out from COVID-19 pandemic. First of all western leaders, don’t have time to devote to conflict and peace processes, while focused on domestic issues. The UK prime minister has only recently recovered from the virus as I write.

It is thought the COVID-19 pandemic will ‘wreak havoc’ in fragile states, where civil society is not strong. While on one hand there is a sense that ‘we’re in this together’, as we know from our own situation in the UK the virus has also given rise to more surveillance and unusually heavy-handed policing. In a country where ethnic tensions turn into armed conflict, there is a danger that ‘othering’, in which particular groups, such as migrants for example, are blamed for spreading the virus, becomes violent and deadly.

Despite prisoner swaps between the Taliban and the Afghan government completed as a foundation for peace talks, and despite the Taliban joining in the campaign to educate citizens about the virus, attacks such as this one by ISIS, continue. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reports 5 covert US air or drone strikes against the Taliban in March, resulting in between 30 and 65 deaths. A month ago, the UN Secretary-General called for ‘an immediate global ceasefire in all corners of the world’. Ongoing ceasefire and peace negotiations are vital for Afghanistan during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Henrietta Cullinan writes on behalf of Voices for Creative Nonviolence-UK (http://vcnv.org.uk), VCNV’s sister organization in the United Kingdom. When visiting Afghanistan, she is a guest of the Afghan Peace Volunteers (www.ourjourneytosmile.com)